Samidoun Network Special Report from Occupied Palestine

Introduction: The Continuous Confrontation

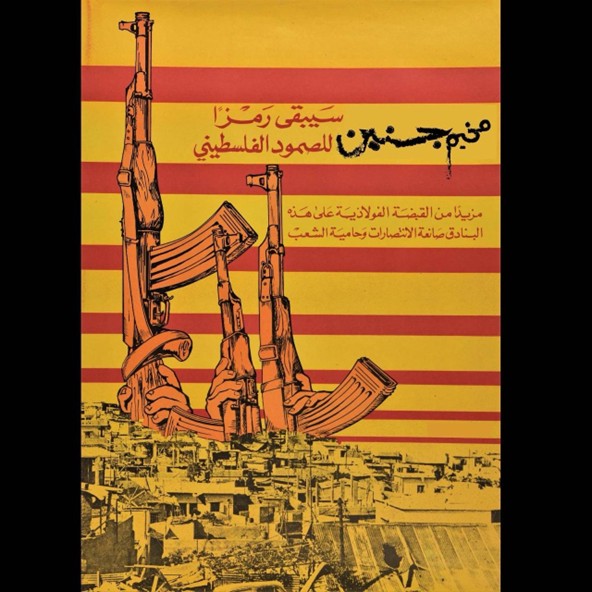

Twenty years after the Second Intifada, the enemy did not imagine that the special forces unit that would storm Jenin to assassinate Jamil Al-Amouri and his companion in June 2021 would serve as an unwitting tool of history. That event sparked the mobilization of hundreds of rifles that appeared on the same day to announce the beginning of the stage of liberation of the West Bank.

Following Jamil Al-Amouri’s assassination, the enemy repeated its mistake many times in announcing destructive military campaigns that turned the streets of the northern West Bank into fertile ground for planting explosive devices, the most recent of which was the “Summer Camps” operation, in which the leader Abu Shujaa was martyred. This operation was confronted with fierce resistance, termed “The Terror of the Camps.” The aggression began at 2:00 AM on Wednesday, August 28, 2024. By dawn there were 10 martyrs by aerial bombardment, including fighters from Jenin and Tubas. Zakaria Zubeidi notes in his master’s thesis “The Hunter and the Dragon: Pursuit in the Palestinian Experience 1968-2018” that the enemy intentionally names its operations in order to undermine the morale of the Palestinian people. During the period of the Second Intifada, for example, it gave names to its military attacks on Jenin such as: “Garbage Collection,” “Hunting the Black Rat,” “House of Cards,” “Collapse of the Pyramid,” “Tears of the Dragon,” and even “A Colorful Journey” when Ramallah was bombed in 2002—these came after the “Defensive Shield” operation. Only a few months after “The Terror of the Camps,” the Palestinian Authority launched its security campaign titled “Homeland Protection” to destroy Jenin Refugee Camp.

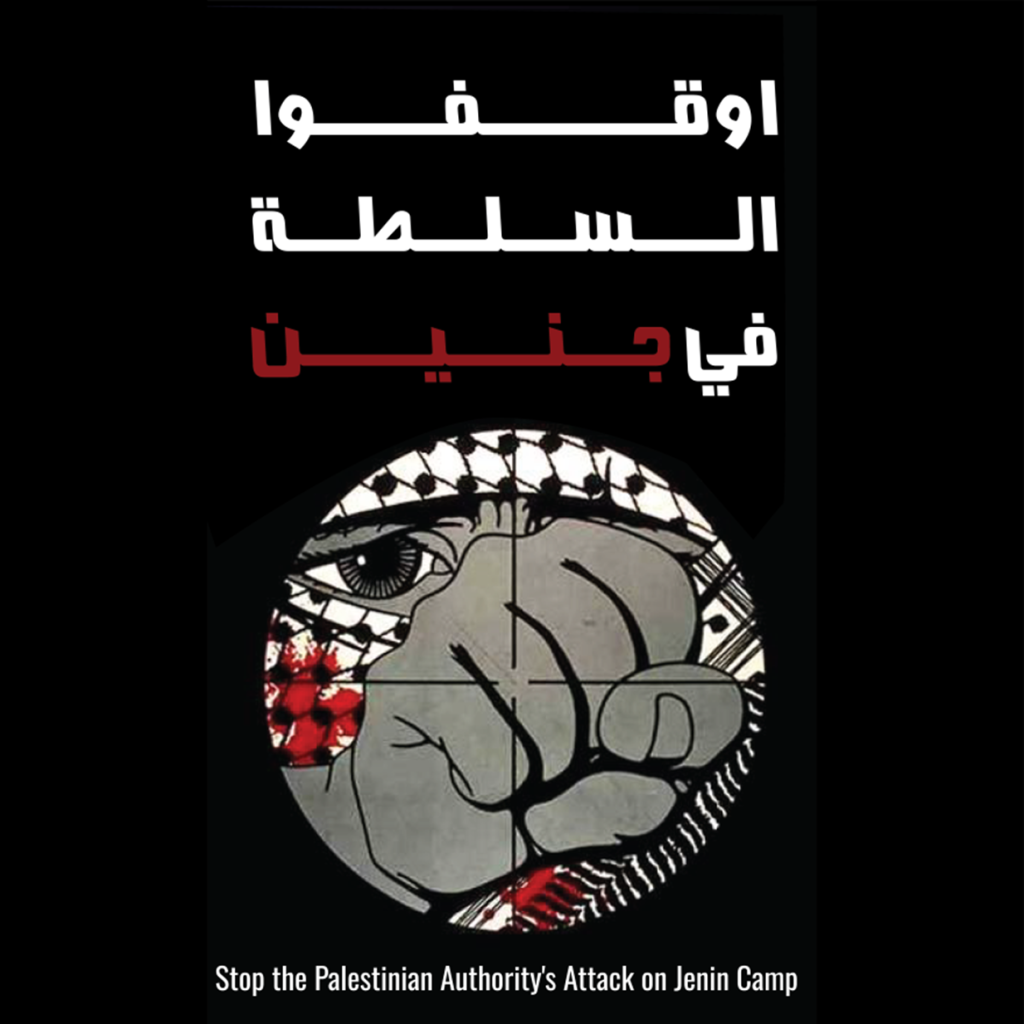

“Protecting the Homeland”: Destroying the Camp

The “Homeland Protection” aggression began on December 9, 2024, and has so far resulted in the martyrdom of journalist Shatha Al-Sabagh , the wanted struggler Yazid Ja’ayseh, Mohammed Al-Jalqamousi and his son Qasem, Mohammed Abu Labda, Majd Zaidan, Ribhi Al-Shalabi, the boy Mohammed Al-Amer, and Sa’ida Abu Bakr. The month-long campaign has relied on imposing a siege on Jenin Refugee Camp, arresting journalists including Obada Tahaineh and Jarrah Khalaf, and detaining 247 young men from Jenin, according to statements by the security services. It also banned Al Jazeera from covering and broadcasting events, deployed snipers on rooftops, stationed armored vehicles, occupied hospitals, terrorized residents with tear gas, cracked down on protests or solidarity movements, launched a smear campaign in the media, silenced dissent, and punished anyone supporting the resistance.

Perhaps the most extraordinary and perplexing aspect is the idea of a Palestinian-imposed siege on a refugee camp—a phenomenon entirely unprecedented in Palestinian history. While Palestinian history is replete with examples of tragic sieges, such as those in Tel Al-Zaatar, Sabra and Shatila, the War of the Camps, and the blockade of Gaza since 1967, as well as repeated sieges of West Bank camps during the 1980s and the battles of the Second Intifada, this is the first instance of a Palestinian siege on a refugee camp. In this aggression against Jenin Refugee Camp, the Palestinian Authority has surpassed itself and assumed the role historically played by the enemies of the Palestinian people.

Since the inception of the Palestinian Authority project, the discourse of statehood and citizenship has taken up a significant space in Palestinian society in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. By the late 1990s, university programs were established to teach human rights, law, and democracy, alongside the emergence of organizations and institutions promoting citizenship, freedoms, and human rights, such as the The Independent Commission for Human Rights (1993) and The Coalition for Integrity and Accountability (AMAN) (2000). According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, there are no less than 10,637 practicing lawyers in the West Bank, in addition to hundreds of graduates of law, international law and human rights annually from Palestinian universities.

Despite this, the aggression has shown that the Palestinian Authority has completely dismantled the legal framework, nullifying the concepts of citizenship, the right to life, fair trial, and all agreements against torture, freedom of opinion, and expression. The aggression began under the pretext of targeting “outlaws,” but the actions primarily entrenched a state of chaos and lawlessness imposed by the Authority itself. It besieged thousands of civilian refugees, cutting off electricity, water, fuel, food, freedom of movement, education, and access to healthcare. Violent practices included killings, arbitrary arrests, beatings, humiliation, and house burnings. The Palestinian Authority relied on its popular base, primarily composed of members of the Fateh movement, to push its political agenda accompanying the aggression on Jenin Refugee Camp through intimidating and using violence against people, as seen in An-Najah National University, Birzeit University, and several cities and villages. This was accompanied by displays of violence and threats during Fateh’s anniversary celebrations.

The killing of martyr Rabhi Al-Shalabi, the wanted struggler Yazeed Ja‘aysa, and journalist Shatha Al-Sabagh—who was the sister of Hamas martyr Moatasem Billah Sabagh—revealed the deliberate intent behind premeditated killings and executions as part of the aggression’s objectives to impose control through bloodshed. Although the Palestinian Authority announced in August 2024 its intention to form a delegation to visit Gaza in an attempt to end the genocidal war, its failure to provide any assistance to Gaza and the changes that occurred on the support fronts pushed it to directly participate in the aggression against the Palestinian people rather than lifting the siege imposed upon them. Instead of sending a delegation to Gaza, the Authority’s security apparatus set forth to besiege Jenin Refugee Camp and kill its residents.

In addition, the Palestinian Authority’s discourse can be classified as self-deception toward itself and the Palestinian people, justifying violence that cannot be justified. The Authority’s attempts to contain the resistance in the north have persisted since its emergence in 2021. These efforts peaked when Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas announced a visit to Jenin Refugee Camp after the Israeli aggression in July 2023. Although such visits held no practical value in strengthening the camp’s resilience, the Authority deemed combating the resistance as a higher priority—or so it was instructed by the American and Israeli administrations.

The narrative of “outlaws” represents the height of this self-deception. First, what law are we talking about? Why are settlers who burn villages and seize land not considered “outlaws,” and why do the Authority’s armored vehicles not protect the Bedouins of the Jordan Valley or Masafer Yatta? Furthermore, labeling besieged refugees—many of whom are fugitives and relatives of martyrs, prisoners, and the wounded—as “outlaws” aligns with the Israeli narrative against the resistance. This rhetoric distorts symbols of Palestinian society, peaking with the martyrdom of Mohammed Jaber (Abu Shujaa), who was subjected to extensive defamation and propaganda until he was martyred by the Israeli enemy on August 28.

The suppression of journalism—a repressive policy that violates human rights—raises the question: What can journalists in Jenin document during this time? Following the ban on media coverage, many journalists posed this logical question: What do we film? The clear skies despite the smoke rising from nowhere? Or the empty streets for inexplicable reasons? Condemning the resistance in Jenin through the “outlaws” rhetoric contradicts the Palestinian narrative, especially regarding Jenin’s role in Palestinian consciousness. It is on Jenin’s soil where the Syrian Arab revolutionary Izz al-Din al-Qassam and a number of members of his armed group were martyred in 1935 while fighting British colonialism.

Stories from the Battalion: “They were youths who believed in their Lord, and We increased them in guidance”

In his master’s thesis, Zakaria Zubeidi noted that the concept of “pursuit” is a permanent fixture in the vocabulary of Palestinian struggle. Pursuit represents rebellion against colonial time and space by betting on life itself. Through tracing biographies and testimonies, Zubeidi concluded that the fugitive as a “living martyr” played a pivotal role in advancing revolutionary movements worldwide throughout history. When Zubeidi, as a fugitive, wrote these words inspired by the legacy of martyrs and freedom fighters, he could not have imagined that only a few years later, his young son Mohammed would become one of the most prominent fugitives, eventually martyred without being embraced by his father.

When a journalist asked martyr Mohammed Shalabi about the resistance fighters’ fierce willingness to engage in battle even if it led to martyrdom, he responded that this ferocity stems from the enemy itself. “The resistance today fights the fiercest enemy in history, equipped with unprecedented destructive capabilities it uses daily against Palestinians in Gaza.” The martyr Mohammed Shalabi, a lawyer from Silat Al-Harthiya, held a bachelor’s degree in law from the University of Jordan and a master’s in international law from the American University in Jenin. He decided to join the battalion and was martyred on the road to al-Quds on March 3 of this year.

Wissam Khazem, a resistance martyr with Norwegian citizenship, lived in Norway for ten years. He is an engineer, married, with children. He decided to join the resistance under the slogan “Existence is Resistance,” which was engraved on his rifle. He is the cousin of the martyr Raad Khazem, who carried out the Tel Aviv operation on April 7, 2022, and the martyr Nidal Khazem, the commander of the Qassam Brigades, who was assassinated by a special force along with Yousef Shraim on March 16, 2023. Wissam was martyred on August 30, 2024, after his car was targeted in the town of Al-Zababdeh while he was with freed prisoner Maysara Musharqa and Arafat Al-Amer.

Arafat Al-Amer was unparalleled in his loyalty to the martyrs. After the martyrdom of key leaders and founders such as Mohammed Hawashin, Mohammed Zubeidi, Islam Khamaiseh, Ahmed Barakat, Wi’am Hanoun, Aysar and Ayham Al-Amer, some began to feel fear and hesitation in continuing on this path. However, Arafat Al-Amer’s devotion was unmatched. When recalling any memory of a martyr, tears would flow from his eyes, and he eagerly anticipated joining them.

As for the child martyr Lujain Musleh, her last appearance was from the window of her house in Kafr Dan on September 4 when the enemy soldiers shot her in the head at the age of sixteen years old. Her father recalls that, since the age of ten, she always longed for martyrdom. Whenever she saw a funeral procession for a martyr in her town of Kafr Dan, Jenin, or Gaza, she would say, “I wish I could have a procession like that.”

The rural areas that the enemy tried to neutralize served as a supportive environment for the battalion in Jenin Camp. They caused such exhaustion to the enemy that it resorted to using aerial weapons to target martyr Laith Shawahneh in the village of Silat Al-Harthiya. The Tubas Battalion, too, offered its finest fighters as martyrs, including Mohammed Zubeidi, Ahmed Fawaz, Qusay Abdul-Razzaq, Mohammed Abu Zagha (from Jenin Camp), Mohammed Awad, and Mohammed Abu Zeina. Days later, several young fighters from the Sawafteh family followed, including Mohammed Sawafteh, Majd Sawafteh, Yassin Sawafteh, and Qais Sawafteh, who was named after martyr Qais Adwan — one of the fighters of the Qassam Brigades at An-Najah University who was martyred on April 4, 2002.

Talabah Bsharat, a school student, would make explosive devices daily until September 11 when he was martyred when a drone targeted him alongside three young men near Al-Tawheed Mosque in Tubas. As for the martyrs Mohammed Abu Talal (Harboush) and Amjad Al-Qanari, they set up an ambush in the Al-Damj neighborhood in Jenin Camp, killing an invading occupation officer and injuring several others during the “Summer Camps” operation.

Conclusion

In his book “The Great Battle of Jenin Camp 2002: Living History,” Jamal Huwail presents in his conclusion the idea that the military defeat that occurred at the end of the battle must be read in light of the broader defeat outside the camp, specifically, within the doctrine of the Palestinian Authority’s national project.

Initially, the leadership of the security apparatus did not participate in devising military plans to defend the camp. This responsibility was left to the resistance fighters and some members of the security forces, relying on minimal experience without scientific planning. Regarding armament, the Authority, even at the height of the Second Intifada, did not arm the resistance, to the point that it prevented weapons stockpiled in the headquarters of the security services from reaching the resistance fighters. By the eve of the Zionist invasion of the camp, the resistance had only one RPG shell.

During the battle, and at the height of the resistance’s sense of victory following an ambush that killed 13 Zionist soldiers, calls from some Authority leaders urged surrender, claiming the futility of continued fighting, even participating in psychological warfare. In the end, Abu Jandal was executed on the twelfth day.

The main difference between the 2002 battle and the current Jenin Battalion experience lies in the reality that the resistance is now directly besieged by the Palestinian security apparatus. Not only has the Authority refrained from supporting the resistance, but it has actively worked to besiege it for years, culminating in the ongoing aggression of more than a month, marked by direct military and political siege. As for the second factor, it is the battalion’s decision to confront to the end, which is derived from the resistance forces from Gaza, which draw from a deep legacy and regional power spearheaded by the Yemeni armed forces. Yemen has developed technologies and combat theories capable of confronting the world’s most powerful states.

Discover more from Samidoun: Palestinian Prisoner Solidarity Network

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.